The beating of a liquid to a foam is not unique to a chocolate-and-water mixture. Neither is it something that works with any random liquid. What you need is an emulsion or a colloid which contains something that can hold the bubbles of the foam, and

- has the right proportion of that "something" to the liquid part

- has the right particle/droplet size

- is being processed at the right temperature (or change of temperatures, for example a sponge cake is a foam that has to start at room temperature and then get heated to first expand and then set into a stabilized state).

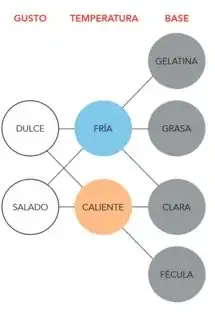

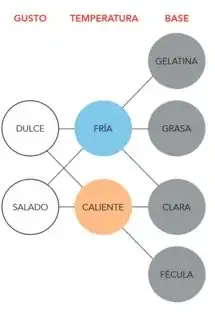

Ferran Adria has created this very simplified diagram:

Translated from the "base" column, the diagram states that you need the proper amount of gelatin, fat, egg white or starch for a foam. The not-so simple version is that

- binders other than gelatin will also work

- protein suspensions other than egg whites will work (e.g. the notorious aquafaba)

- when you have a liquid which has more than one of these, all bets are off. It might be helpful for making the foam (e.g. in chocolate, you have both starch and fat), or be detrimental (e.g. if you get fat in your egg whites), or show different behavior depending on ratios (you can make hot protein-based foams with milk, but if you remove its water to make cream, it is only suited for cold fat-based foams).

The way you foam your food also matters, some liquids will foam with beating, others will require a siphon. Also, some foams are stable for a long time, others have to be served immediately before they liquefy again.

All in all, foams are a very complex topic, and for any given liquid that comes across your way, it is unlikely that you can just pick it and make it into a mousse. If you want to create foams, use a recipe, these are tested to work.