I've not come up against clear explanations when trying to think about a situation where an ice sheet is advancing and comes up against a cliff. What happens next? How does the ice sheet cross the cliff? Does the base get stuck?

Does it create some landforms into the original cliff-face? The forcing that would apply should be very strong (and perhaps it will continue to apply over a very long time period). Also, how does the flow of the glacier happen in these locations? Will the cliff-face be exposed to liquid water flow throughout the period that the ice sheet has covered it, and won't this cause very rapid erosion of the cliff-surface?

From a geologic perspective, this would have been happening across the Baltic Clint though most of these cliffs are in the range of 15–25 meters—in other words, relatively small for an ice sheet to cross. However, there are also some exposed (presently above-water) parts which are slightly higher.

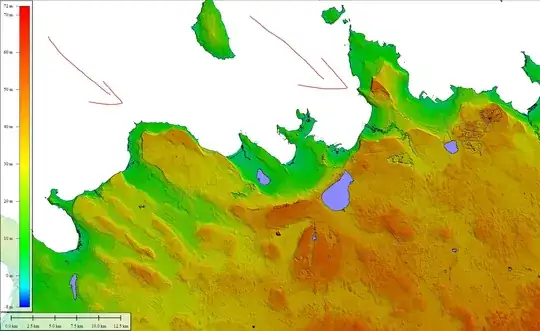

I've put a small map (20m DEM; generally one front of cliffs by the modern coastline and then occasional ones further inland) below which illustrates where this would have been happening during the last glaciation period based on the example of Tallinn, Estonia, though by no means is this the only place where such a situation would have occurred.

Of course, the DEM has further problems, including that ~20k years of isostatic uplift has raised these a fair bit since so the actual obstacle that the ice sheets met should have been smaller (perhaps was: are the remnant limestone mounds the part that didn't get washed away?).

I also find the sentence (from the above Wikipedia page) weird:

However it is not known to which degree the Baltic Klint originated in postglacial time or if it evolved from cliff-like forms sculpted by the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet. In Gotland 20th century cliff retreat rates have been estimated at 0.15 to 0.78 cm/year.

I don't see how the ice sheet's advance/retreat could have caused such a cliff if the limestone plateau did not exist there beforehand.

I'm not expecting an answer based on this location specifically, but rather perhaps there are some imaged cliff-faces in Greenland/Antarctica where this behaviour has been recorded presently? I tried some searches and found this which seems relevant but I wasn't able to access the full text.