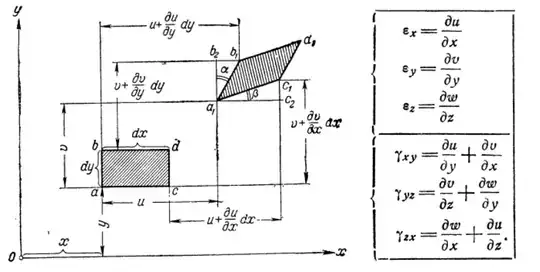

The answer to this lies in the defining equation for the strains that you have supplied. The full displacement gradient $u_{i,j}$ (where the $\bullet_{,j}$ represents the $j^{\rm th}$ derivative) can be linearly decomposed into a symmetric and an anti-symmetric component: $u_{i,j} = \epsilon_{i,j} + \omega_{i,j}$, in the usual way as for all rank-2 tensors.

The symmetric part, $\epsilon_{i,j} = \frac{u_{i,j}+u_{j,i}}{2}$ represents the strain, the only thing that counts for elastic energy, whereas the anti-symmetric part $\omega_{i,j} = \frac{u_{i,j}-u_{j,i}}{2}$ represents rigid body rotation. And as you remarked, this costs no energy to the system. Hence, for elasticity, we only ever talk about $\epsilon_{i,j}$.