I used to think that Hooke's law was a relationship between how much a bar under uniaxial loading deformed and the internal force (per unit area) that developed within that bar. But this clearly isn't the case as I have recently seen that Hooke's law is used in analyzing the stress in pure bending of beams. So it seems that Hooke's law is a lot more general than I had thought.

If Hooke's law isn't specifically defined for a bar under uniaxial loading, what physical object is it exactly defined for? What system/object is Hooke's law trying to describe?

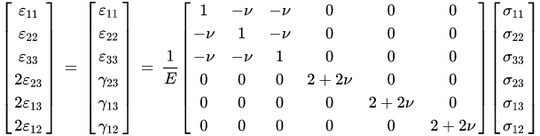

My guess is that Hooke's law is defined for an infinitesimal cubic element which feels a normal stress on its sides from neighboring elements (picture below). That is, Hooke's law relates the normal stress and normal strain on an infinitesimal cubic element. This might make Hooke's law general enough so that it could be applied to many loading situations since we can think of any object as being made of many of these infinitesimal elements and the total strain of the object is the sum of the strains of all of the elements. Is this correct? I'd appreciate it if someone could clear this up for me.