If I model this as a simply supported beam having load at mid span [...]

I suspect that this is where your analysis went awry.

First off, you should always model bridges with distributed loads, not a single concentrated load at midspan. The most significant load on a bridge will almost always be its own self-weight; load-trains are heavy but, well, so are bridges.

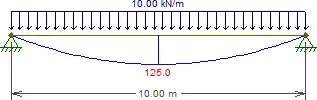

Secondly, I assume you're thinking of the bridge like this:

Indeed, we can see here that the bending moment is greater at midspan.

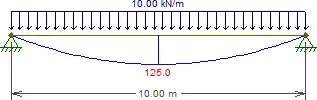

However, that's not the bridge we're looking at, it's missing the cantilevers! So in fact we get:

Now, I chose a midspan-to-cantilever ratio which exactly cancels out the bending moment at midspan. It's entirely possible that the real bridge has a positive bending moment at midspan, but it'll certainly be much smaller than the negative moment at the supports.

(the cantilevers might actually be supported at the ends; that would reduce the negative moment at the central supports and therefore increase the positive moment at midspan, but it'd still be much lower than if it were a pure simply-supported beam)

Obviously, the moment envelope from the load-train will have a positive component at midspan, but it won't be anything the thinner cross-section can't handle.

All diagrams created with Ftool, a free, educational 2D frame analysis tool.